Myst (series)

| Myst | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Cyan Worlds (Myst, Riven, Uru, V) Presto Studios (III) Ubisoft (IV) |

| Publisher(s) | Broderbund (1993–1996) Red Orb Entertainment (1997–2000) Ubisoft (2000–2007) Cyan Worlds (2008–) |

| Creator(s) | Rand Miller Robyn Miller |

| Composer(s) | Robyn Miller (Myst, Riven) Jack Wall (III, IV) Tim Larkin (Uru, V) |

| Platform(s) | Windows, Mac, consoles, iOS, Android |

| First release | Myst (1993)[1] |

| Latest release | Riven (2024) |

Myst is a franchise centered on a series of adventure video games. The first game in the series, Myst, was released in 1993 by brothers Rand and Robyn Miller and their video game company Cyan, Inc. The first sequel to Myst, Riven, was released in 1997 and was followed by three more direct sequels: Myst III: Exile in 2001, Myst IV: Revelation in 2004, and Myst V: End of Ages in 2005. A spinoff featuring a multiplayer component, Uru: Ages Beyond Myst, was released in 2003 and followed by two expansion packs.

Myst's story concerns an explorer named Atrus who has the ability to write books that serve as links to other worlds, known as Ages. This practice of creating linking books was developed by an ancient civilization known as the D'ni, whose society crumbled after being ravaged by disease. The player takes the role of an unnamed person referred to as the Stranger and assists Atrus by traveling to other Ages and solving puzzles. Over the course of the series, Atrus writes a new Age for the D'ni survivors to live on, and players of the games set the course the civilization will follow.

The brothers developed Myst after producing award-winning games for children. Drawing on childhood stories, the brothers spent months designing the Ages players would investigate. The name Myst came from Jules Verne's novel The Mysterious Island. After Riven was released, Robyn left Cyan to pursue other projects, and Cyan began developing Uru; developers Presto Studios and Ubisoft created Exile and Revelation before Cyan returned to complete the series with End of Ages. Myst and its sequels were critical and commercial successes, selling more than twelve million copies; the games drove sales of personal computers and CD-ROM drives as well as attracting casual gamers with its nonviolent, methodical gameplay. The video games' success has led to three published novels in addition to soundtracks, a comic series, and television and movie pitches.

Plot

[edit]

| Myst story chronology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Myst's story begins with the arrival of a people known as the D'ni on Earth, almost 10,000 years ago. The D'ni /dəˈniː/ are an ancient race who used a special skill to create magical books that serve as portals to the worlds they describe, known as Ages. The D'ni build a great city and thriving civilization in caverns. A young geologist from the surface, Anna, stumbled upon the D'ni civilization. Learning the D'ni language, Anna becomes known as Ti'ana and marries a D'ni named Aitrus; the couple have a son named Gehn. Soon after, D'ni is ravaged by a plague created by a man named A'Gaeris. Aitrus sacrifices himself to save his wife and child, killing A'Gaeris while Ti'ana and Gehn escape to the surface as the D'ni civilization falls.[2]

Ti'ana raises Gehn until he runs away as a teenager, learning the D'ni Art of writing descriptive books. Ti'ana also cares for Gehn's son, Atrus, until Gehn arrives to teach Atrus the Art. Atrus realizes that his father is reckless and power-hungry, and with the help of Ti'ana and a young woman, Catherine, Atrus traps Gehn on his Age of Riven with no linking books. Atrus and Catherine marry and have two children, Sirrus and Achenar. The brothers grow greedy, and, after plundering their father's Ages, they trap Catherine on Riven. When Atrus returns to investigate, the brothers strand him in a D'ni cavern before they themselves are trapped by special "prison" books. Through the help of a Stranger, Atrus is freed and sends his benefactor to Riven to retrieve Catherine from the clutches of Gehn.[2] Sirrus and Achenar are punished for their crimes by being imprisoned in separate Ages until they reform.[3]

Atrus writes a new Age called Releeshahn for the D'ni survivors to rebuild their civilization as he and Catherine settle back on Earth, raising a daughter named Yeesha. As Atrus prepares to take the Stranger to Releeshahn, a mysterious man named Saavedro appears and steals the Releeshahn Descriptive Book. The Stranger follows Saavedro through several Ages (which were used to train Sirrus and Achenar in the art of writing Ages) before finally recovering the book. Ten years later, Atrus asks for the Stranger's help in determining if his sons have repented after their lengthy imprisonment; the Stranger saves Yeesha from Sirrus's machinations, but Sirrus and a repentant Achenar are killed. D'ni is not fully restored until the creatures the D'ni enslaved, known as the Bahro, are freed.

Games

[edit]| Game | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release year | Developer | Platforms | ||

| Myst | 1993 | Cyan | 3DO, AmigaOS, CD-i, iOS, Jaguar CD, Mac, Nintendo DS, Nintendo 3DS, PlayStation, PSP, Saturn, Windows, Windows Mobile, Android | |

| The first game in the Myst series was the eponymous Myst, developed by Cyan, Inc. and Broderbund. Originally released in 1993 for Macintosh and PC platforms, the game was later ported or remade for the Saturn, Windows, Jaguar CD, 3DO, CD-i, PlayStation, AmigaOS, PSP, Nintendo DS, Nintendo 3DS and iPhone. In Myst, players travel across Ages using a point-and-click interface, using the mouse to interact with puzzle objects such as switches or gears.[4] | ||||

| Riven | 1997 | Cyan | Mac OS, PlayStation, Saturn, Windows, iOS, Android | |

| Flush with the success of Myst, Cyan moved to a new office and began work on Riven, which was released in 1997. Like Myst, Riven was a commercial and critical success, selling more than 4.5 million units.[5] | ||||

| Myst III: Exile | 2001 | Presto Studios | Mac OS, Mac OS X, PlayStation 2, Windows, Xbox | |

| The third game of the series, Myst III: Exile, was developed by Presto Studios and published by Ubisoft in 2001. Exile continued with the frame-based method of player movement, but used a game engine to allow a 360-degree field of view from any point.[6] Exile was a commercial success (though not to the extent of Myst or Riven),[7] selling millions of units. | ||||

| Uru: Ages Beyond Myst | 2003 | Cyan Worlds | Windows | |

| Uru: Ages Beyond Myst was a departure from the previous games in the series, featuring graphics rendered in real time and a third-person camera. Through avatar customization, players could create their own character to solve puzzles and uncover story information.[8] Uru was to ship with a massively multiplayer online portion, Uru Live, but the initial release was canceled shortly before the single-player aspect was released. Uru Live was rereleased in several incarnations, being canceled each time. Cyan Worlds currently operates the servers for latest iteration of the MMO, MO:ULagain, which is free to play. The running costs are covered through player donations.

Though initially well-received, Uru was considered a financial disappointment. Its expansion packs and originality earned the title a cult following.[9] In 2011, Cyan Worlds and OpenUru.org announced the release of Myst Online's client and 3ds Max plugin under the GNU GPL v3 license.[10] | ||||

| Myst IV: Revelation | 2004 | Ubisoft | Mac OS X, Windows, Xbox | |

| Myst IV: Revelation was produced entirely by Ubisoft, and marked a return to the prerendered graphics of Exile.[11] Since the studio had little experience with such games, Ubisoft hired new employees who had experience in the field.[12] The game was seen as an improvement over Uru,[13][14] and was favorably received upon release. | ||||

| Myst V: End of Ages | 2005 | Cyan Worlds | Windows, Mac OS X | |

| Cyan returned to develop Myst V: End of Ages, billed as the final game in the series.[15] As with Uru, End of Ages featured graphics rendered in real time, allowing uninhibited player movement. Three control methods were offered to players, similar to those respectively used in Myst, Exile and Uru.[16] The game was judged a fitting end to the series, though a lack of financial backing for new, non-Myst projects nearly caused Cyan to shut down before the release of the game.[17] | ||||

Development

[edit]

Myst was originally conceptualized by brothers Rand and Robyn Miller. The Millers had created fictional worlds and stories as young children, influenced by the works of authors such as J. R. R. Tolkien, Robert A. Heinlein, and Isaac Asimov.[18] They formed a video game company together called Cyan, Inc.; their first game, called The Manhole, won the Software Publishers Association award in 1988 for best use of the digital medium. Cyan produced other games, aimed at children; the Millers eventually decided their next project would be made for adults.[19]

The brothers spent months designing the Ages comprising the game,[20] which were influenced by earlier whimsical "worlds" Cyan had made for children's games.[21] The game's name, as well as the overall solitary and mysterious atmosphere of the island, was inspired by the book The Mysterious Island by Jules Verne.[19] Robyn's unfinished novel, Dunnyhut, influenced aspects of Myst's story,[22] which was developed bit by bit as the brothers conceptualized the various worlds.[22] As development progressed, the Millers realized that they would need to have even more story and history than would be revealed in the game itself.[21] Realizing that fans would enjoy getting a deeper look at the story not in the games, the Millers produced a rough draft of what would become a novel, Myst: The Book of Atrus.[22]

After the enormous response to Myst, work quickly began on the next Myst game. Cyan moved from their garage to a new office and hired additional programmers, designers, and artists.[23] The game was to ship in late 1996, but the release was pushed back a year.[24] Development costs were between $5 and $10 million, many times Myst's budget.[25] After the release of Riven, Robyn Miller left the company to pursue other projects, while Rand stayed behind to work on a Myst franchise.[26]

While Rand Miller stated Cyan would not make another sequel to Myst, Mattel (then the owner of the Myst franchise) offered the task of developing a sequel to several video game companies who created detailed story proposals and technology demonstrations.[27] Presto Studios, makers of the Journeyman Project adventure games, was hired to develop Myst III. Presto spent millions developing the game and used the studio's entire staff to complete the project, which took two and a half years to develop.[27] Soon after Myst III: Exile was released, Presto was shut down,[28] and Exile publisher Ubisoft developed the sequel, Myst IV: Revelation, internally.[29] Meanwhile, Cyan produced the spinoff title Uru: Ages Beyond Myst, which included an aborted multiplayer component allowing players to cooperatively solve puzzles.

Cyan returned to produce what was billed as the final game in the series,[15] discarding live action sequences embedded in prerendered graphics for a world rendered in real time. The actors' faces were turned into textures and mapped onto digital characters, with the actor's actions synchronized by motion capture. Shortly before release, Cyan closed down development,[30] although this did not impact the release of the game; the company was able to rehire its employees a few weeks later, and continued to work on non-Myst projects[15] and an attempted resurrection of Uru's multiplayer component, Myst Online. Servers paid for by donation were set up in 2010, and the game went open-source in 2011.

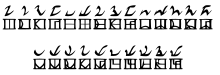

Among the detailed elements of the Myst universe Cyan created was the language and culture of the D'ni. The civilization's numbers and writing first appeared in Riven, and were important to solving some of the game's puzzles.[31] The D'ni language was the language presented in various games and novels of the Myst franchise, created by Richard A. Watson. Several online D'ni dictionaries have been developed as part of the ongoing fan-based culture associated with the game.[32]

Music

[edit]The music for each game in the Myst series has fallen to various composers. Originally, the Millers believed that any music or sound besides ambient noise would distract the player from the game and ruin the sense of reality; Myst, therefore, was to have no music at all. A sound test eventually persuaded the developers that music heightened the sense of immersion rather than lessening it, and as such Robyn Miller composed 40 minutes of synthesized music for the game.[20] He would also produce the music for Riven, which featured leitmotifs for each of the main characters. Virgin Records bought the rights to the music and produced the soundtracks,[33] which were released in 1998.

For Myst III: Exile and Myst IV: Revelation, composer Jack Wall created the music, developing a more active musical style different from Miller's ambient themes. Wall looked at the increasing complexity of games as an opportunity to give players a soundtrack with as much force as a movie score,[34] and tried to create a distinctive sound that was still recognizable as Myst music.[5] In Revelation, Wall adapted the themes for the recurring characters of Myst,[35] and collaborated with Peter Gabriel, who provided a song to the game as well as voicework.[36]

The music for Uru: Ages Beyond Myst and Myst V: End of Ages was composed by Tim Larkin, who had gotten involved in the series doing sound design for Riven.[37] Larkin stepped away from his background as a jazz composer and musician to create music with less structure and without a definite beginning and end.[38] Larkin created different music depending on the location, giving each setting and Age a distinctive tone.[37] For End of Ages, Larkin was unable to afford a full orchestra to perform his score, so he combined individual instrumentation with an array of synthesizers.[39]

Adaptations

[edit]Rand and Robyn Miller both wanted to develop Myst's back story into novels. After the success of Myst, publisher Hyperion signed a three-book, US$1 million deal with the brothers. David Wingrove worked from the Miller brothers' story outlines. The three books — Myst: The Book of Atrus, Myst: The Book of Ti'ana, and Myst: The Book of D'ni — were released in 1995, 1996, and 1997, respectively.[40] The books were later packaged together as The Myst Reader. A fourth novel, Myst: The Book of Marrim, was planned but has not surfaced.

Cyan partnered with Dark Horse Comics in 1993 to release a four-part comic series called Myst: The Book of Black Ships. The series would have focused on Atrus and his young sons, taking place before the events of Myst. The first issue was released on September 3, 1997,[41] but further books were canceled after Cyan decided the first issue did not live up to expectations.[40] Another comic, Myst #0: Passages, was later released online.[40]

Disney approached Cyan Worlds about constructing a theme park inspired by Myst, which included scouting an island area within Disney's Florida properties that Rand Miller felt was perfect for the Myst setting.[42]

Various proposals for films and television series based on the franchise were planned or rumored but never came to fruition. They include:

- The Sci Fi Channel announced a TV miniseries in 2002,[43] but it never materialized. According to Rand Miller, none of the various proposals met Cyan's approval, or were too formulaic or silly.[44]

- Independent filmmakers Patrick McIntire and Adrian Vanderbosch wanted to produce a motion picture based on the story revealed in the Myst novels and in 2006 sent a DVD proposal to Cyan[45] The film was set to be based on the novel Myst: The Book of Ti'ana,[46] but no longer appears to be in production.[47]

- In 2014, Legendary Entertainment announced that it was developing a television series based on Myst, but nothing came of it.[48]

In May 2015, Unwritten: Adventures in the Ages of MYST and Beyond was published by Inkworks Productions as an authorized,[49] Myst-based pencil-and-paper role-playing game. Unwritten was built on the popular Fate Core RPG system with a focus on investigation and non-violent adventure. Two small supplements exist as background for game-players: The D'Ni Primer explaining the history of the D'Ni, and The Myst Saga giving a chronology of the Myst series.

In 2016, Cyan Worlds released the Kickstarter-backed Obduction. While Obduction is not narratively linked to Myst, the game was considered by Rand Miller to be a spiritual successor to the Myst series, borrowing several of its themes and puzzle-design approaches, as well as incorporating full-motion video in homage to Myst. Robyn, who had left Cyan before this point, collaborated to help score the game and take on the role of one of the in-game characters.[50]

In anticipation of the first game's 25th anniversary in September 2018, Cyan Worlds secured the necessary rights to release all of the Myst games, updated for modern Windows systems with assistance of GOG.com to be released as a collected physical collectors edition.[51] Further, Cyan launched a Kickstarter in April 2018 to provide digital copies of the seven games as well as backer rewards including a simulated Linking Book, using an LCD screen inserted into a book binding.[52] The Kickstarter was successfully funded, bringing in US$2.8 million on a US$250,000 target goal.[53]

On June 26, 2019, Village Roadshow Entertainment Group announced that they have acquired the rights to the franchise and plans to expand its mythology to develop a multi-platform universe that includes movies and TV series. They will work alongside Miller and his brother Ryan as well as Isaac Testerman and Yale Rice of Delve Media.[54]

Reception and impact

[edit]| Game | Metacritic[55] | GameRankings[56] |

|---|---|---|

| Myst | n/a | 82.57% |

| Riven | 83% | 84.60% |

| Myst III: Exile | 83% | 77.07% |

| Uru: Ages Beyond Myst | 79% | 76.19% |

| Uru: The Path of the Shell | 72% | 67.69% |

| Uru: Complete Chronicles | n/a | 84.67% |

| Myst IV: Revelation | 82% | 81.72% |

| Myst V: End of Ages | 80% | 79.82% |

| Myst Online: Uru Live (GameTap) | 78% | 82.67% |

Overall, the Myst series has been critically and commercially successful. Rand and Robyn Miller were expecting Myst to perform as well as previous Cyan titles, making enough money to fund the next project.[57] Instead, Myst sold more than six million units, becoming the top-selling PC game of all time until The Sims surpassed Myst sales in 2002.[58] The first three games in the series have sold more than twelve million copies.

1UP.com writer Jeremy Parish noted that there have been two main opinions of Myst's slow, puzzle-based gameplay; "Fans consider Myst an elegant, intelligent game for grown-ups, while detractors call it a soulless stroll through a digital museum, more art than game."[59] Game industry executives were confused by Myst's success, not understanding how an "interactive slide show" turned out to be a huge hit. Online magazine writer Russell Pitts of The Escapist called Myst "unlike anything that had come before, weaving video almost seamlessly into a beautifully rendered world, presenting a captivating landscape filled with puzzles and mystery. In a game market dominated by Doom clones and simulators, Myst took us by the hand and showed us the future of gaming. It took almost a decade for anyone to follow its lead."[60] Critics from Wired and Salon considered the games approaching the level of art,[61][62] while authors Henry Jenkins and Lev Manovich pointed out the series as exemplifying the promise of new media to create unseen art forms.[63][64]

The series caused a major shift in the adventure game genre. Unlike previous games, Myst attempted to keep players immersed in the world by removing all information not associated with the fictional world itself—no explanatory text, inventory, or score counters.[65] Myst has also been cited as the reason for the decline of the adventure game genre; eager to capitalize on Myst's success, publishers churned out mediocre Myst clones, which flooded the market.[66] By Exile's release, games like Myst were considered to be an "antiquated" form of gaming by some critics.[67]

The title was widely credited as one of the first games to appeal not just to hardcore gamers but to casual players and demographics that generally did not play games, such as women.[26] Myst's lack of conventional game elements—violence, dying, and failure—appealed to nongamers and those contemplating buying a computer.[68] The Millers' decision to develop Myst for the nascent CD-ROM format helped boost interest and adoption of disc drives.[69]

The game inspired a CD parody game called Pyst, written by comedian Peter Bergman and featured John Goodman in video scenes.[70] Players traveled across the spoiled island of Myst after millions of players walked over it, with the parody game poking fun at elements of the prototype.[71]

Fan conventions

[edit]

The game has spawned annual fan conventions around the world. Mysterium has been held since 2000, which grew out of the plans of a small group of fans who wanted to meet in person. Approximately 200 people attended the meeting in Spokane, Washington, which was held at the headquarters of Cyan Worlds, developers of the game. Subsequent conventions have been more formally planned, involving presentations and live music.[72] Similar to Mysterium, Mystralia is a gathering for Australia and New Zealand and has been held since 2005.

References

[edit]- ^ Maher, Jimmy (February 21, 2020). "Myst (or, The Drawbacks to Success)". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Staff (November 1, 2004). "'Myst IV: Revelation': A Family Affair". Apple Inc. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ Castro, Juan (October 4, 2004). "Myst IV Revelation Review; Is the latest adventure worth the trip?". IGN. Archived from the original on October 13, 2004. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Cyan, Inc (1993). Myst User Manual. Manipulating Objects (Windows version ed.). Broderbund. pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Pham, Alex (May 17, 2001). "Game Design; Adding Texture, Detail to Miller Brothers' Legacy". Los Angeles Times. p. T4.

- ^ Presto Studios (2001). Myst III: Exile - User's Manual. Playing the Game (PC/Mac ed.). Ubisoft. p. 4.

- ^ Odelius, Dwight (January 8, 2004). "Game is magical and immersive - and nonviolent". Houston Chronicle. p. 3.

- ^ Krause, Staci (December 4, 2003). "Uru: Ages Beyond Myst Review (page 1)". IGN. Archived from the original on December 17, 2003. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- ^ Jenkins, David (September 5, 2005). "Report: Cyan Worlds Slims To 'Skeleton Crew'". Gamasutra. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ^ "CyanWorlds.com Engine - OpenUru". wiki.openuru.org. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ Adams, Dan (May 12, 2004). "E3 2004: Myst IV: Revelations". IGN. Archived from the original on August 3, 2004. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ Lord, Geneviève (April 21, 2005). "Postmortem: Myst IV: Revelation". Gamasutra. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Staff (November 19, 2004). "PC Reviews: Myst IV Revelation". Computer and Video Games. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ Parish, Jeremy (October 5, 2004). "Reviews: Myst IV: Revelation - Finally, it's cool to like Myst again". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c Sowa, Tom (January 12, 2005). "Cyan Worlds ends one story, ponders new one". The Spokesman-Review. p. A8.

- ^ Chu, Karen (September 25, 2005). "Myst V: End of Ages (PC)". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2008.

- ^ Fahey, Rob (September 30, 2005). "Myst developer Cyan Worlds is back from the brink". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ Gardner, Fran (November 7, 1995). "Book by Myst Brothers Unveils Atrus' world before the game". The Oregonian. p. E1.

- ^ a b Carroll, John (August 1994). "Guerrillas in the Myst". Wired. Vol. 2, no. 8.

- ^ a b Miller, Rand and Robyn; Cyan (1993). The Making of Myst (CR-RPM). Cyan/Broderbund.

- ^ a b Stern, Gloria (August 23, 1994). "Through the Myst". WorldVillage.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- ^ a b c Lovece, Frank (November 26, 1995). "Read 'Myst'y for Me". Newsday. p. 28.

- ^ Miller Bros., Cyan, &c (1997). The Making of Riven: The Sequel to Myst (CD-ROM). Cyan/Broderbund.

- ^ Carroll, John (September 1997). "(D)Riven". Wired. Vol. 5, no. 9. pp. 1–15.

- ^ Takashi, Dean (August 26, 1997). "Can Myst's Sequel Live Up to Expectations?". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b Lillington, Karen (March 2, 1998). "'Myst' partnership is riven". Salon. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Uhler, Greg (October 2001). "Presto Studios' Myst III: Exile". Game Developer. 8 (10): 40–47.

- ^ Saladino, Michael (December 2002). "And presto... it's gone!". Game Developer. 9 (12): 44–49.

- ^ Castro, Juan (April 5, 2004). "Myst IV Announced". IGN. Archived from the original on April 8, 2004. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Thorson, Thor (September 6, 2005). "Cyan Worlds slashes staff, suspends development". GameSpot. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ Ficara, Ken (October 31, 1997). "Breathtaking Sequel to 'Myst' Lacks Its Sense of Exploration". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ Pearce, Celia (2006). "Productive Play: Game Culture From the Bottom Up". Games and Culture. 1 (17): 17. doi:10.1177/1555412005281418. S2CID 16084255.

- ^ Thomas, David (May 8, 1998). "Mastermind of Myst, Riven also has a talent for music". The Denver Post.

- ^ Wall, Jack (January 11, 2002). "Music for Myst III: Exile - The Evolution of a Videogame Soundtrack (page 1)". Gamasutra. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ^ Miller, Jennifer. "Interview with Jack Wall - Myst IV Composer". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Ubisoft (August 22, 2004). "Myst IV Revelation Features Original Peter Gabriel Song and Voice Talent". Business Wire.

- ^ a b Miller, Jennifer. "Interview with Tim Larkin". Just Adventure. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ^ Gutoff, Bija. "Tim Larkin: Composing Myst's Musical World (page 3)". Apple, Inc. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ^ Staff (September 1, 2005). "Interview with Myst V audio director and composer Tim Larkin". Music4Games. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c Cook, Brad (April 1, 2001). "The Lost Ages: Myst 3 Revealed (page 2)". Apple, Inc. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ "Profiles: Myst: The Book of Black Ships #1 (of 4)". Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved June 29, 2008.

- ^ Hughes, William (September 10, 2016). "Myst creator Rand Miller on his favorite puzzle that everybody hates". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- ^ NBC Universal (April 2, 2002). "SCI FI Channel Announces Ambitious New Slate of Original Movies and Miniseries". Sci Fi Channel.

- ^ Sowa, Tom (May 10, 2008). "Avoiding Hollywood, Cyan Worlds allows two fans to develop a Myst movie". The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ Crigger, Lara. "'Myst' Opportunity". 1UP.com. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- ^ "Defining Cyan's Involvement" (Press release). Mysteria Film Group. February 1, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ "Myst Movie Drama". The Gameshelf. May 7, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Graser, Marc (October 7, 2014). "Series Based on 'Myst' Games in Development at Legendary". Variety. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "Cyan Ventures acquires Unwritten: Adventures in the Ages of Myst and Beyond". Cyan Worlds. November 26, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Dingman, Hayman (October 4, 2014). "Exclusive preview: This is 'Obduction,' Cyan's spiritual successor to 'Myst'". PC World. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Horti, Samuel (March 17, 2018). "Cyan is releasing updated versions of all the Myst games to mark series' 25th anniversary". PC Gamer. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ Kuchera, Ben (April 9, 2018). "Myst Kickstarter offers $1,000 tier that's actually worth it". Polygon. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ Chalk, Andy (June 29, 2018). "Myst 3 and 4 finally come to GOG, Cyan is planning new games in the series". PC Gamer. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ "Village Roadshow Developing 'Myst' Video Game Into Multi-Platform Film & TV Universe". Deadline. June 26, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ Riven, Exile, Revelation, End of Ages, Uru: Ages Beyond Myst, Uru: The Path of the Shell, and Myst Online: Uru Live on Metacritic. Accessed on September 14, 2014. All scores for Windows PC versions of the games.

- ^ Myst, Riven, Exile, Revelation, End of Ages, Uru: Ages Beyond Myst, Uru: The Path of the Shell, Myst: Uru Complete Chronicles, and Myst Online: Uru Live on GameRankings. Accessed on September 14, 2014. All scores for Windows PC versions of the games.

- ^ Miller, Robyn (2007). "The Secret History of 'Myst'". Make. 8 (1): 54–61.

- ^ Walker, Trey (March 22, 2002). "The Sims overtakes Myst". GameSpot. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ "Myst IV: Revelation Review". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ Pitts, Russell (July 8, 2008). "A Three-Year History of Gaming". The Escapist. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ Miller, Laura (November 6, 1997). "Riven Rapt". Salon. Archived from the original on April 2, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (December 4, 1994). "A New Art Form May Arise From the 'Myst'". The New York Times. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ Jenkins, Henry; Tara McPherson, Jane Shattuc (2002). Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture. Duke University Press. p. 494. ISBN 0-8223-2737-6.

- ^ Manovich, Lev (2002). The Language of New Media. MIT Press. p. 244. ISBN 0-262-63255-1.

- ^ Wolf, Mark (2007). The Video Game Explosion: A History from Pong to Playstation and Beyond. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-0-313-33868-7.

- ^ Staff (January 12, 2005). "The Essential 50 Part 33: Myst". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ Hamilton, Anita (August 9, 2004). "Secrets of The New Myst". Time. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ Staff. "History of Myst; 10 years and counting". Tiscali.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ Staff (August 1, 2000). "RC Retroview: Myst". IGN. Archived from the original on February 17, 2002. Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ^ Schwartz, Bruce (October 10, 1996). "Seeing through the 'Myst'-tique 'Pyst' pokes fun at hit CD-ROM". USA Today.

- ^ Eng, Paul M (October 21, 1996). "Myst Gets Dissed on CD-ROM". BusinessWeek.

- ^ "Myst"ified fans find parity in fantastic worlds, Deseret Morning News, Scott Iwasaki, August 28, 2006

External links

[edit]