North Sea

| North Sea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Western Europe and Northern Europe |

| Coordinates | 56°N 3°E / 56°N 3°E |

| Type | Sea |

| Primary inflows | Baltic Sea, Elbe, Weser, Ems, Rhine/Waal, Meuse, Scheldt, Spey, Don, Dee, Tay, Forth, Tyne, Wear, Tees, Humber, Thames |

| Basin countries | United Kingdom (specifically England and Scotland), Norway, Denmark, Germany (specifically Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein), the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Czech Republic |

| Max. length | 960 km (600 mi) |

| Max. width | 580 km (360 mi) |

| Surface area | 570,000 km2 (220,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 95 m (312 ft) |

| Max. depth | 700 m (2,300 ft) |

| Water volume | 54,000 km3 (4.4×1010 acre⋅ft) |

| Salinity | 3.4 to 3.5% |

| Max. temperature | 18 °C (64 °F) |

| Min. temperature | 6 °C (43 °F) |

| References | Seatemperature.org and Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences |

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Sea in the north. It is more than 970 kilometres (600 mi) long and 580 kilometres (360 mi) wide, covering 570,000 square kilometres (220,000 sq mi).

It hosts key north European shipping lanes and is a major fishery. The coast is a popular destination for recreation and tourism in bordering countries, and a rich source of energy resources, including wind and wave power.

The North Sea has featured prominently in geopolitical and military affairs, particularly in Northern Europe, from the Middle Ages to the modern era. It was also important globally through the power northern Europeans projected worldwide during much of the Middle Ages and into the modern era. The North Sea was the centre of the Vikings' rise. The Hanseatic League, the Dutch Republic, and Britain all sought to gain command of the North Sea and access to the world's markets and resources. As Germany's only outlet to the ocean, the North Sea was strategically important through both world wars.

The coast has diverse geology and geography. In the north, deep fjords and sheer cliffs mark much of its Norwegian and Scottish coastlines respectively, whereas in the south, the coast consists mainly of sandy beaches, estuaries of long rivers and wide mudflats. Due to the dense population, heavy industrialisation, and intense use of the sea and the area surrounding it, various environmental issues affect the sea's ecosystems. Adverse environmental issues – commonly including overfishing, industrial and agricultural runoff, dredging, and dumping, among others – have led to several efforts to prevent degradation and to safeguard long-term economic benefits.

Geography

The North Sea is bounded by the Orkney Islands and east coast of Great Britain to the west[1] and the northern and central European mainland to the east and south, including Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France.[2] In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean.[1][2] In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat,[2] narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively.[1] In the north it is bordered by the Shetland Islands, and connects with the Norwegian Sea, which is a marginal sea in the Arctic Ocean.[1][3]

The North Sea is more than 970 kilometres (600 mi) long and 580 kilometres (360 mi) wide, with an area of 750,000 square kilometres (290,000 sq mi) and a volume of 54,000 cubic kilometres (13,000 cu mi).[4] Around the edges of the North Sea are sizeable islands and archipelagos, including Shetland, Orkney, and the Frisian Islands.[2] The North Sea receives freshwater from a number of European continental watersheds, as well as the British Isles. A large part of the European drainage basin empties into the North Sea, including water from the Baltic Sea. The largest and most important rivers flowing into the North Sea are the Elbe and the Rhine – Meuse.[5] Around 185 million people live in the catchment area of the rivers discharging into the North Sea encompassing some highly industrialized areas.[6]

Major features

For the most part, the sea lies on the European continental shelf with a mean depth of 90 metres (300 ft).[1][7] The only exception is the Norwegian trench, which extends parallel to the Norwegian shoreline from Oslo to an area north of Bergen.[1] It is between 20 and 30 kilometres (12 and 19 mi) wide and has a maximum depth of 725 metres (2,379 ft).[8]

The Dogger Bank, a vast moraine, or accumulation of unconsolidated glacial debris, rises to a mere 15 to 30 m (50 to 100 ft) below the surface.[9][10] This feature has produced the finest fishing location of the North Sea.[1] The Long Forties and the Broad Fourteens are large areas with roughly uniform depth in fathoms (forty fathoms and fourteen fathoms or 73 and 26 m or 240 and 85 ft deep, respectively). These great banks and others make the North Sea particularly hazardous to navigate,[11] which has been alleviated by the implementation of satellite navigation systems.[12] The Devil's Hole lies 320 kilometres (200 mi) east of Dundee, Scotland. The feature is a series of asymmetrical trenches between 20 and 30 kilometres (12 and 19 mi) long, one and two kilometres (0.6 and 1.2 mi) wide and up to 230 metres (750 ft) deep.[13]

Other areas which are less deep are Cleaver Bank, Fisher Bank and Noordhinder Bank.

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the North Sea as follows:[14]

On the Southwest. A line joining the Phare de Walde (Walde Lighthouse, in France, 50°59'37"N, 1°54'53"E) and Leathercoat Point (England, 51°10'01.4"N 1°24'07.8").[15] northeast of Dover.

On the Northwest. From Dunnet Head (58°40'20"N, 3°22'30"W) in Scotland to Tor Ness (58°47'N) in the Island of Hoy, thence through this island to the Kame of Hoy (58°55'N) on to Breck Ness on Mainland (58°58'N) through this island to Costa Head (3°14'W) and Inga Ness (59'17'N) in Westray through Westray, to Bow Head, across to Mull Head (North point of Papa Westray) and on to Seal Skerry (North point of North Ronaldsay) and thence to Horse Island (South point of the Shetland Islands).

On the North. From the North point (Fethaland Point) of the Mainland of the Shetland Islands, across to Graveland Ness (60°39'N) in the Island of Yell, through Yell to Gloup Ness (1°04'W) and across to Spoo Ness (60°45'N) in Unst island, through Unst to Herma Ness (60°51'N), on to the SW point of the Rumblings and to Muckle Flugga (60°51′N 0°53′W / 60.850°N 0.883°W) all these being included in the North Sea area; thence up the meridian of 0°53' West to the parallel of 61°00' North and eastward along this parallel to the coast of Norway, the whole of Viking Bank is thus included in the North Sea.

On the East. The Western limit of the Skagerrak [A line joining Hanstholm (57°07′N 8°36′E / 57.117°N 8.600°E) and the Naze (Lindesnes, 58°N 7°E / 58°N 7°E)].

Hydrology

Temperature and salinity

• Tide times after Bergen (negative = before)

• The three amphidromic centers

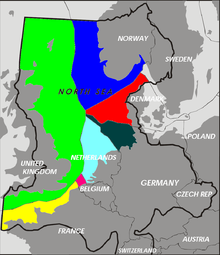

• Coasts:

marshes = green

mudflats = greenish blue

lagoons = bright blue

dunes = yellow

sea dikes= purple

moraines near the coast= light brown

rock-based coasts = greyish brown

The average temperature is 17 °C (63 °F) in the summer and 6 °C (43 °F) in the winter.[4] The average temperatures have been trending higher since 1988, which has been attributed to climate change.[16][17] Air temperatures in January range on average between 0 and 4 °C (32 and 39 °F) and in July between 13 and 18 °C (55 and 64 °F). The winter months see frequent gales and storms.[1]

The salinity averages between 34 and 35 grams per litre (129 and 132 g/US gal) of water.[4] The salinity has the highest variability where there is fresh water inflow, such as at the Rhine and Elbe estuaries, the Baltic Sea exit and along the coast of Norway.[18]

Water circulation and tides

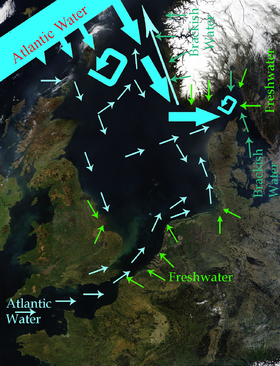

The main pattern to the flow of water in the North Sea is an anti-clockwise rotation along the edges.[19]

The North Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean receiving the majority of ocean current from the northwest opening, and a lesser portion of warm current from the smaller opening at the English Channel. These tidal currents leave along the Norwegian coast.[20] Surface and deep water currents may move in different directions. Low salinity surface coastal waters move offshore, and deeper, denser high salinity waters move inshore.[21]

The North Sea located on the continental shelf has different waves from those in deep ocean water. The wave speeds are diminished and the wave amplitudes are increased. In the North Sea there are two amphidromic systems and a third incomplete amphidromic system.[22][23] In the North Sea the average tide difference in wave amplitude is between zero and eight metres (26 ft).[An average is a single figure, not a range.][4]

The Kelvin tide of the Atlantic Ocean is a semidiurnal wave that travels northward. Some of the energy from this wave travels through the English Channel into the North Sea. The wave continues to travel northward in the Atlantic Ocean, and once past the northern tip of Great Britain, the Kelvin wave turns east and south and once again enters the North Sea.[24]

| Tidal range (m) (from calendars) |

Maximum tidal range (m) | Tide-gauge | Geographical and historical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.79–1.82 | 2.39 | Lerwick[25] | Shetland Islands |

| 2.01–3.76 | 4.69 | Aberdeen[26] | Mouth of River Dee in Scotland |

| 2.38–4.61 | 5.65 | North Shields[27] | Mouth of Tyne estuary |

| 2.31–6.04 | 8.20 | Kingston upon Hull[28] | Northern side of Humber estuary |

| 1.75–4.33 | 7.14 | Grimsby[29] | Southern side of Humber estuary farther seaward |

| 1.98–6.84 | 6.90 | Skegness[30] | Lincolnshire coast north of the Wash |

| 1.92–6.47 | 7.26 | King's Lynn[31] | Mouth of Great Ouse into the Wash |

| 2.54–7.23 | Hunstanton[32] | Eastern edge of the Wash | |

| 2.34–3.70 | 4.47 | Harwich[33] | East Anglian coast north of Thames Estuary |

| 4.05–6.62 | 7.99 | London Bridge[34] | Inner end of Thames Estuary |

| 2.38–6.85 | 6.92 | Dunkerque[35] | Dune coast east of the Strait of Dover |

| 2.02–5.53 | 5.59 | Zeebrugge[36] | Dune coast west of Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta |

| 3.24–4.96 | 6.09 | Antwerp[37] | Inner end of the southernmost estuary of Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta |

| 1.48–1.90 | 2.35 | Rotterdam[38] | Borderline of estuary delta[39] and sedimentation delta of the Rhine |

| 1.10–2.03 | 2.52 | Katwijk[40] | Mouth of the Uitwateringskanaal of the Oude Rijn into the sea |

| 1.15–1.72 | 2.15 | Den Helder[41] | Northeastern end of Holland dune coast west of IJsselmeer |

| 1.67–2.20 | 2.65 | Harlingen[42] | East of IJsselmeer, outlet of IJssel river, the eastern branch of the Rhine |

| 1.80–2.69 | 3.54 | Borkum[43] | Island in front of Ems river estuary |

| 2.96–3.71 | Emden[44] | East side of Ems river estuary | |

| 2.60–3.76 | 4.90 | Wilhelmshaven[45] | Jade Bight |

| 2.66–4.01 | 4.74 | Bremerhaven[46] | Seaward end of Weser estuary |

| 3.59–4.62 | Bremen-Oslebshausen[47] | Bremer Industriehäfen, inner Weser estuary | |

| 3.3–4.0 | Bremen Weser barrage[48] | Artificial tide limit of river Weser, 4 km upstream of the city centre | |

| 2.6–4.0 | Bremerhaven 1879[49] | Before start of Weser Correction (Weser straightening works) | |

| 0–0.3 | Bremen city centre 1879[49] | Before start of Weser Correction (Weser straightening works) | |

| 1.45 | Bremen city centre 1900[50] | Große Weserbrücke, 5 years after completion of Weser Correction works | |

| 2.54–3.48 | 4.63 | Cuxhaven[51] | Seaward end of Elbe estuary |

| 3.4–3.9 | 4.63 | Hamburg St. Pauli[52][53] | St. Pauli Piers, inner part of Elbe estuary |

| 1.39–2.03 | 2.74 | Westerland[54] | Sylt island, off the Nordfriesland coast |

| 2.8–3.4 | Dagebüll[55] | Coast of Wadden Sea in Nordfriesland | |

| 1.1–2.1 | 2.17 | Esbjerg[56][57] | Northern end of Wadden Sea in Denmark |

| 0.5–1.1 | Hvide Sande[56] | Danish dune coast, entrance of Ringkøbing Fjord lagoon | |

| 0.3–0.5 | Thyborøn[56] | Danish dune coast, entrance of Nissum Bredning lagoon, part of Limfjord | |

| 0.2–04 | Hirtshals[56] | Skagerrak. Hanstholm and Skagen have the same values. | |

| 0.14–0.30 | 0.26 | Tregde[58] | Skagerrak, southern end of Norway, east of an amphidromic point |

| 0.25–0.60 | 0.65 | Stavanger[58] | North of that amphidromic point, tidal rhythm irregular |

| 0.64–1.20 | 1.61 | Bergen[58] | Tidal rhythm regular |

Coasts

The eastern and western coasts of the North Sea are jagged, formed by glaciers during the ice ages. The coastlines along the southernmost part are covered with the remains of deposited glacial sediment.[1] The Norwegian mountains plunge into the sea creating deep fjords and archipelagos. South of Stavanger, the coast softens, the islands become fewer.[1] The eastern Scottish coast is similar, though less severe than Norway. From north east of England, the cliffs become lower and are composed of less resistant moraine, which erodes more easily, so that the coasts have more rounded contours.[59][60] In the Netherlands, Belgium and in East Anglia the littoral is low and marshy.[1] The east coast and south-east of the North Sea (Wadden Sea) have coastlines that are mainly sandy and straight owing to longshore drift, particularly along Belgium and Denmark.[61]

Coastal management

The southern coastal areas were originally flood plains and swampy land. In areas especially vulnerable to storm surges, people settled behind elevated levees and on natural areas of high ground such as spits and geestland.[62]: [302, 303] As early as 500 BC, people were constructing artificial dwelling hills higher than the prevailing flood levels.[62]: [306, 308] It was only around the beginning of the High Middle Ages, in 1200 AD, that inhabitants began to connect single ring dikes into a dike line along the entire coast, thereby turning amphibious regions between the land and the sea into permanent solid ground.[62]

The modern form of the dikes supplemented by overflow and lateral diversion channels, began to appear in the 17th and 18th centuries, built in the Netherlands.[63] The North Sea Floods of 1953 and 1962 were the impetus for further raising of the dikes as well as the shortening of the coast line so as to present as little surface area as possible to the punishment of the sea and the storms.[64] Currently, 27% of the Netherlands is below sea level protected by dikes, dunes, and beach flats.[65]

Coastal management today consists of several levels.[66] The dike slope reduces the energy of the incoming sea, so that the dike itself does not receive the full impact.[66] Dikes that lie directly on the sea are especially reinforced.[66] The dikes have, over the years, been repeatedly raised, sometimes up to 9 metres (30 ft) and have been made flatter to better reduce wave erosion.[67] Where the dunes are sufficient to protect the land behind them from the sea, these dunes are planted with beach grass (Ammophila arenaria) to protect them from erosion by wind, water, and foot traffic.[68]

Storm tides

Storm surges threaten, in particular, the coasts of the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Denmark and low-lying areas of eastern England particularly around The Wash and Fens.[61] Storm surges are caused by changes in barometric pressure combined with strong wind created wave action.[69]

The first recorded storm tide flood was the Julianenflut, on 17 February 1164. In its wake, the Jadebusen, (a bay on the coast of Germany), began to form. A storm tide in 1228 is recorded to have killed more than 100,000 people.[70] In 1362, the Second Marcellus Flood, also known as the Grote Manndrenke, hit the entire southern coast of the North Sea. Chronicles of the time again record more than 100,000 deaths, large parts of the coast were lost permanently to the sea, including the now legendary lost city of Rungholt.[71] In the 20th century, the North Sea flood of 1953 flooded several nations' coasts and cost more than 2,000 lives.[72] 315 citizens of Hamburg died in the North Sea flood of 1962.[73]: [79, 86]

Tsunamis

Though rare, the North Sea has been the site of a number of historically documented tsunamis. The Storegga Slides were a series of underwater landslides, in which a piece of the Norwegian continental shelf slid into the Norwegian Sea. The immense landslips occurred between 8150 BCE and 6000 BCE, and caused a tsunami up to 20 metres (66 ft) high that swept through the North Sea, having the greatest effect on Scotland and the Faeroe Islands.[74][75] The Dover Straits earthquake of 1580 is among the first recorded earthquakes in the North Sea measuring between 5.6 and 5.9 on the Richter scale. This event caused extensive damage in Calais both through its tremors and possibly triggered a tsunami, though this has never been confirmed. The theory is a vast underwater landslide in the English Channel was triggered by the earthquake, which in turn caused a tsunami.[76] The tsunami triggered by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake reached Holland, although the waves had lost their destructive power. The largest earthquake ever recorded in the United Kingdom was the 1931 Dogger Bank earthquake, which measured 6.1 on the Richter magnitude scale and caused a small tsunami that flooded parts of the British coast.[76]

Geology

Shallow epicontinental seas like the current North Sea have since long existed on the European continental shelf. The rifting that formed the northern part of the Atlantic Ocean during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, from about 150 million years ago, caused tectonic uplift in the British Isles.[77] Since then, a shallow sea has almost continuously existed between the uplands of the Fennoscandian Shield and the British Isles.[78] This precursor of the current North Sea has grown and shrunk with the rise and fall of the eustatic sea level during geologic time. Sometimes it was connected with other shallow seas, such as the sea above the Paris Basin to the south-west, the Paratethys Sea to the south-east, or the Tethys Ocean to the south.[79]

During the Late Cretaceous, about 85 million years ago, all of modern mainland Europe except for Scandinavia was a scattering of islands.[80] By the Early Oligocene, 34 to 28 million years ago, the emergence of Western and Central Europe had almost completely separated the North Sea from the Tethys Ocean, which gradually shrank to become the Mediterranean as Southern Europe and South West Asia became dry land.[81] The North Sea was cut off from the English Channel by a narrow land bridge until that was breached by at least two catastrophic floods between 450,000 and 180,000 years ago.[82][83] Since the start of the Quaternary period about 2.6 million years ago, the eustatic sea level has fallen during each glacial period and then risen again. Every time the ice sheet reached its greatest extent, the North Sea became almost completely dry, the dry landmass being known as Doggerland, whose northern regions were themselves known to have been glaciated.[84] The present-day coastline formed after the Last Glacial Maximum when the sea began to flood the European continental shelf.[85]

In 2006 a bone fragment was found while drilling for oil in the North Sea. Analysis indicated that it was a Plateosaurus from 199 to 216 million years ago. This was the deepest dinosaur fossil ever found and the first find for Norway.[86]

-

Map showing hypothetical extent of Doggerland (c. 8,000 BC), which provided a land bridge between Great Britain and continental Europe

-

North Sea from De Koog, Texel island

Nature

Fish and shellfish

Copepods and other zooplankton are plentiful in the North Sea. These tiny organisms are crucial elements of the food chain supporting many species of fish.[87] Over 230 species of fish live in the North Sea. Cod, haddock, whiting, saithe, plaice, sole, mackerel, herring, pouting, sprat, and sandeel are all very common and are fished commercially.[87][88] Due to the various depths of the North Sea trenches and differences in salinity, temperature, and water movement, some fish such as blue-mouth redfish and rabbitfish reside only in small areas of the North Sea.[89]

Crustaceans are also commonly found throughout the sea. Norway lobster, deep-water prawns, and brown shrimp are all commercially fished, but other species of lobster, shrimp, oyster, mussels and clams all live in the North Sea.[87] Recently non-indigenous species have become established including the Pacific oyster and Atlantic jackknife clam.[88]

Birds

The coasts of the North Sea are home to nature reserves including the Ythan Estuary, Fowlsheugh Nature Preserve, and Farne Islands in the UK and the Wadden Sea National Parks in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands.[87] These locations provide breeding habitat for dozens of bird species. Tens of millions of birds make use of the North Sea for breeding, feeding, or migratory stopovers every year. Populations of black-legged kittiwakes, Atlantic puffins, northern gannets, northern fulmars, and species of petrels, seaducks, loons (divers), cormorants, gulls, auks, and terns, and many other seabirds make these coasts popular for birdwatching.[87][88]

Marine mammals

The North Sea is also home to marine mammals. Common seals, grey seals, and harbour porpoises can be found along the coasts, at marine installations, and on islands. The very northern North Sea islands such as the Shetland Islands are occasionally home to a larger variety of pinnipeds including bearded, harp, hooded and ringed seals, and even walrus.[90] North Sea cetaceans include various porpoise, dolphin and whale species.[88][91]

Flora

Plant species in the North Sea include species of wrack, among them bladder wrack, knotted wrack, and serrated wrack. Algae, macroalgal, and kelp, such as oarweed and laminaria hyperboria, and species of maerl are found as well.[88] Eelgrass, formerly common in the entirety of the Wadden Sea, was nearly wiped out in the 20th century by a disease.[92] Similarly, sea grass used to coat huge tracts of ocean floor, but have been damaged by trawling and dredging have diminished its habitat and prevented its return.[93] Invasive Japanese seaweed has spread along the shores of the sea clogging harbours and inlets and has become a nuisance.[94]

Biodiversity and conservation

Due to the heavy human populations and high level of industrialization along its shores, the wildlife of the North Sea has suffered from pollution, overhunting, and overfishing. Flamingos and pelicans were once found along the southern shores of the North Sea, but became extinct over the second millennium.[95] Walruses frequented the Orkney Islands through the mid-16th century, as both Sable Island and Orkney Islands lay within their normal range.[96] Grey whales also resided in the North Sea but were driven to extinction in the Atlantic in the 17th century[97] Other species have dramatically declined in population, though they are still found. North Atlantic right whales, sturgeon, shad, rays, skates, salmon, and other species were common in the North Sea until the 20th century, when numbers declined due to overfishing.[98][99]

Other factors like the introduction of non-indigenous species, industrial and agricultural pollution, trawling and dredging, human-induced eutrophication, construction on coastal breeding and feeding grounds, sand and gravel extraction, offshore construction, and heavy shipping traffic have also contributed to the decline.[88] For example, a resident orca pod was lost in the 1960s, presumably due to the peak in PCB pollution in this time period.[100]

The OSPAR commission manages the OSPAR convention to counteract the harmful effects of human activity on wildlife in the North Sea, preserve endangered species, and provide environmental protection.[101] All North Sea border states are signatories of the MARPOL 73/78 Accords, which preserve the marine environment by preventing pollution from ships.[102] Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands also have a trilateral agreement for the protection of the Wadden Sea, or mudflats, which run along the coasts of the three countries on the southern edge of the North Sea.[103]

Names

The North Sea has had various names throughout history. One of the earliest recorded names was Septentrionalis Oceanus, or "Northern Ocean", which was cited by Pliny.[104] He also noted that the Cimbri called it Morimarusa – "Dead Sea".[105] The name "North Sea" probably came into English, however, via the Dutch Noordzee, who named it thus either in contrast with the Zuiderzee ("South Sea"), located south of Frisia, or because the sea is generally to the north of the Netherlands. Before the adoption of "North Sea", the names used in English were "German Sea" or "German Ocean", referred to as the Latin names Mare Germanicum and Oceanus Germanicus,[106] and these persisted in use until the First World War.[107] Other common names in use for long periods were the Latin terms Mare Frisicum, as well as the English equivalent, "Frisian Sea".[108][109] The modern names of the sea in the other local languages are: Danish: Vesterhavet, lit. 'West Sea' [ˈvestɐˌhɛˀvð̩] or Nordsøen [ˈnoɐ̯ˌsøˀn̩], Dutch: Noordzee, Dutch Low Saxon: Noordzee, French: Mer du Nord, West Frisian: Noardsee, German: Nordsee, Low German: Noordsee, North Frisian: Weestsiie, lit. 'West Sea', Swedish: Nordsjön, Bokmål: Nordsjøen [ˈnûːrˌʂøːn], Nynorsk: Nordsjøen, Scots: North Sea and Scottish Gaelic: An Cuan a Tuath.

-

A 1482 recreation of a map from Ptolemy's Geography showing the "Oceanus Germanicus"

-

Edmond Halley's solar eclipse 1715 map showing The German Sea

History

Early history

The North Sea has provided waterway access for commerce and conquest. Many areas have access to the North Sea because of its long coastline and the European rivers that empty it.[1] There is little documentary evidence concerning the North Sea before the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 CE, however, archaeological evidence reveals the diffusion of cultures and technologies from across or along the North Sea to Great Britain and Scandinavia and reliance by some prehistoric cultures on fishing, whaling, and seaborne trade on the North Sea. The Romans established organised ports in Britain, which increased shipping and began sustained trade[110] the diffusion of cultures and technologies from across or along the North Sea to Great Britain and Scandinavia and reliance by some prehistoric cultures on fishing, whaling, and seaborne trade on the North Sea. The Romans established organised ports in Britain, which increased shipping and began sustained trade[110] and many Scandinavian tribes participated in raids and wars against the Romans and Roman coinage and manufacturing were important trade goods. When the Romans abandoned Britain in 410, the Germanic Angles, Frisians, Saxons, and Jutes began the next great migration across the North Sea during the Migration Period. They made successive invasions of the island from what is now the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany.[111]

The Viking Age began in 793 with the attack on Lindisfarne; for the next quarter-millennium, the Vikings ruled the North Sea. In their superior longships, they raided, traded, and established colonies and outposts along the coasts of the sea. From the Middle Ages through the 15th century, the northern European coastal ports exported domestic goods, dyes, linen, salt, metal goods and wine. The Scandinavian and Baltic areas shipped grain, fish, naval necessities, and timber. In turn, the North Sea countries imported high-grade cloths, spices, and fruits from the Mediterranean region.[112] Commerce during this era was mainly conducted by maritime trade due to underdeveloped roadways.[112]

In the 13th century the Hanseatic League, though centred on the Baltic Sea, started to control most of the trade through important members and outposts on the North Sea.[113] The League lost its dominance in the 16th century, as neighbouring states took control of former Hanseatic cities and outposts. Their internal conflict prevented effective cooperation and defence.[114] As the League lost control of its maritime cities, new trade routes emerged that provided Europe with Asian, American, and African goods.[115][116]

Age of sail

The 17th century Dutch Golden Age saw Dutch maritime power at its zenith.[117][118] Important overseas colonies, a vast merchant marine, a large fishing fleet,[112] powerful navy, and sophisticated financial markets made the Dutch the ascendant power in the North Sea, to be challenged by an ambitious England. This rivalry led to the first three Anglo-Dutch Wars between 1652 and 1673, which ended with Dutch victories.[118] After the Glorious Revolution in 1688, the Dutch prince William ascended to the English throne. With unified leadership, commercial, military, and political power began to shift from Amsterdam to London.[119] The British did not face a challenge to their dominance of the North Sea until the 20th century.[120]

Modern era

Tensions in the North Sea were again heightened in 1904 by the Dogger Bank incident. During the Russo-Japanese War, several ships of the Russian Baltic Fleet, which was on its way to the Far East, mistook British fishing boats for Japanese ships and fired on them, and then upon each other, near the Dogger Bank, nearly causing Britain to enter the war on the side of Japan.

During the First World War, Great Britain's Grand Fleet and Germany's Kaiserliche Marine faced each other in the North Sea,[121] which became the main theatre of the war for surface action.[121] Britain's larger fleet and North Sea Mine Barrage were able to establish an effective blockade for most of the war, which restricted the Central Powers' access to many crucial resources.[122] Major battles included the Battle of Heligoland Bight,[123] the Battle of the Dogger Bank,[124] and the Battle of Jutland.[124] World War I also brought the first extensive use of submarine warfare, and a number of submarine actions occurred in the North Sea.[125]

The Second World War also saw action in the North Sea, though it was restricted more to aircraft reconnaissance and action by fighter/bomber aircraft, submarines and smaller vessels such as minesweepers and torpedo boats.[126][127]

After the war, hundreds of thousands of tons of chemical weapons were disposed of by being dumped in the North Sea.[128]

After the war, the North Sea lost much of its military significance because it is bordered only by NATO member-states. However, it gained significant economic importance in the 1960s as the states around the North Sea began full-scale exploitation of its oil and gas resources.[129] The North Sea continues to be an active trade route.[130]

Economy

Political status

Countries that border the North Sea all claim the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) of territorial waters, within which they have exclusive fishing rights.[131] The Common Fisheries Policy of the European Union (EU) exists to coordinate fishing rights and assist with disputes between EU states and the EU border state of Norway.[132]

After the discovery of mineral resources in the North Sea during the early 1960s, the Convention on the Continental Shelf established country rights largely divided along the median line. The median line is defined as the line "every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured".[133] The ocean floor border between Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark was only reapportioned in 1969 after protracted negotiations and a judgment of the International Court of Justice.[131][134]

Oil and gas

As early as 1859, oil was discovered in onshore areas around the North Sea and natural gas as early as 1910.[80] Onshore resources, for example the K12-B field in the Netherlands continue to be exploited today.

Offshore test drilling began in 1966 and then, in 1969, Phillips Petroleum Company discovered the Ekofisk oil field[135] distinguished by valuable, low-sulphur oil.[136] Commercial exploitation began in 1971 with tankers and, after 1975, by a pipeline, first to Teesside, England and then, after 1977, also to Emden, Germany.[137]

The exploitation of the North Sea oil reserves began just before the 1973 oil crisis, and the climb of international oil prices made the large investments needed for extraction much more attractive.[138] The start in 1973 of the oil reserves by the UK allowed them to stop the declining position in international trade in 1974, and a huge increase after the discovery and exploitation of the huge oil field by Phillips group in 1977 as the Brae field.

Although the production costs are relatively high, the quality of the oil, the political stability of the region, and the proximity of important markets in western Europe have made the North Sea an important oil-producing region.[136] The largest single humanitarian catastrophe in the North Sea oil industry was the destruction of the offshore oil platform Piper Alpha in 1988 in which 167 people lost their lives.[139]

Besides the Ekofisk oil field, the Statfjord oil field is also notable as it was the cause of the first pipeline to span the Norwegian trench.[140] The largest natural gas field in the North Sea, Troll gas field, lies in the Norwegian trench, dropping over 300 metres (980 ft), requiring the construction of the enormous Troll A platform to access it.

The price of Brent Crude, one of the first types of oil extracted from the North Sea is used today as a standard price for comparison for crude oil from the rest of the world.[141] The North Sea contains western Europe's largest oil and natural gas reserves and is one of the world's key non-OPEC producing regions.[142]

In the UK sector of the North Sea, the oil industry invested £14.4 billion in 2013 and was on track to spend £13 billion in 2014. Industry body Oil & Gas UK put the decline down to rising costs, lower production, high tax rates, and less exploration.[143]

In January 2018, The North Sea region contained 184 offshore rigs, which made it the region with the highest number of offshore rigs in the world at the time.[144]

Fishing

The North Sea is Europe's main fishery accounting for over 5% of international commercial fish caught.[1] Fishing in the North Sea is concentrated in the southern part of the coastal waters. The main method of fishing is trawling.[145] In 1995, the total volume of fish and shellfish caught in the North Sea was approximately 3.5 million tonnes.[146] Besides saleable fish, it is estimated that one million tonnes of unmarketable by-catch is caught and discarded to die each year.[147]

In recent decades, overfishing has left many fisheries unproductive, disturbing marine food chain dynamics and costing jobs in the fishing industry.[148] Herring, cod and plaice fisheries may soon face the same plight as mackerel fishing, which ceased in the 1970s due to overfishing.[149] The objective of the European Union Common Fisheries Policy is to minimize the environmental impact associated with resource use by reducing fish discards, increasing the productivity of fisheries, stabilising markets of fisheries and fish processing, and supplying fish at reasonable prices for the consumer.[150]

Whaling

Whaling was an important economic activity from the 9th until the 13th century for Flemish whalers.[151] The medieval Flemish, Basque and Norwegian whalers who were replaced in the 16th century by Dutch, English, Danes, and Germans, took massive numbers of whales and dolphins and nearly depleted the right whales. This activity likely led to the extinction of the Atlantic population of the once common grey whale.[152] By 1902 the whaling had ended.[151] After being absent for 300 years a single grey whale returned in 2010,[153] it probably was the first of many more to find its way through the now ice-free Northwest Passage.

Mineral resources

In addition to oil, gas, and fish, the states along the North Sea also take millions of cubic metres per year of sand and gravel from the ocean floor. These are used for beach nourishment, land reclamation and construction.[154] Rolled pieces of amber may be picked up on the east coast of England.[155]

Renewable energy

Due to the strong prevailing winds, and shallow water, countries on the North Sea, particularly Germany and Denmark, have used the shore for wind power since the 1990s.[156] The North Sea is the home of one of the first large-scale offshore wind farms in the world, Horns Rev 1, completed in 2002. Since then many other wind farms have been commissioned in the North Sea (and elsewhere). As of 2013, the 630 megawatt (MW) London Array is the largest offshore wind farm in the world, with the 504 (MW) Greater Gabbard wind farm the second largest, followed by the 367 MW Walney Wind Farm. All are off the coast of the UK. These projects will be dwarfed by subsequent wind farms that are in the pipeline, including Dogger Bank at 4,800 MW, Norfolk Bank (7,200 MW), and Irish Sea (4,200 MW). At the end of June 2013 total European combined offshore wind energy capacity was 6,040 MW. The UK installed 513.5 MW of offshore wind power in the first half-year of 2013.[157] The development of the offshore wind industry in UK-controlled areas of the North Sea is traced to three phases: coastal, off-coastal and deep offshore in the period 2004 – 2021.[158]

The expansion of offshore wind farms has met with some resistance. Concerns have included shipping collisions[159] and environmental effects on ocean ecology and wildlife such as fish and migratory birds,[160] however, these concerns were found to be negligible in a long-term study in Denmark released in 2006 and again in a UK government study in 2009.[161][162] There are also concerns about reliability,[163] and the rising costs of constructing and maintaining offshore wind farms.[164] Despite these, development of North Sea wind power is continuing, with plans for additional wind farms off the coasts of Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK.[165] There have also been proposals for a transnational power grid in the North Sea[166][167] to connect new offshore wind farms.[168]

Energy production from tidal power is still in a pre-commercial stage. The European Marine Energy Centre has installed a wave testing system at Billia Croo on the Orkney mainland[169] and a tidal power testing station on the nearby island of Eday.[170] Since 2003, a prototype Wave Dragon energy converter has been in operation at Nissum Bredning fjord of northern Denmark.[171]

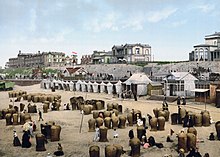

Tourism

The beaches and coastal waters of the North Sea are destinations for tourists. The English, Belgian, Dutch, German and Danish coasts[172][173] are developed for tourism. The North Sea coast of the United Kingdom has tourist destinations with beach resorts and links golf courses; the coastal town of St. Andrews in Scotland as the birthplace of golf is renowned as the "Home of Golf", and is a popular location among golfing pilgrims.[174]

The North Sea Trail is a long-distance trail linking seven countries around the North Sea.[175] Windsurfing and sailing[176] are popular sports because of the strong winds. Mudflat hiking,[177] recreational fishing and birdwatching[173] are among other activities.

The climatic conditions on the North Sea coast have been claimed to be healthy. As early as the 19th century, travellers visited the North Sea coast for curative and restorative vacations. The sea air, temperature, wind, water, and sunshine are counted among the beneficial conditions that are said to activate the body's defences, improve circulation, strengthen the immune system, and have healing effects on the skin and the respiratory system.[178]

The Wadden Sea in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands is an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Marine traffic

The North Sea is important for marine transport and its shipping lanes are among the busiest in the world.[131] Major ports are located along its coasts: Rotterdam, the busiest port in Europe and the fourth busiest port in the world by tonnage as of 2013[update], Antwerp (was 16th) and Hamburg (was 27th), Bremen/Bremerhaven and Felixstowe, both in the top 30 busiest container seaports,[179] as well as the Port of Bruges-Zeebrugge, Europe's leading ro-ro port.[180]

Fishing boats, service boats for offshore industries, sport and pleasure craft, and merchant ships to and from North Sea ports and Baltic ports must share routes on the North Sea. The Dover Strait alone sees more than 400 commercial vessels a day.[181] Because of this volume, navigation in the North Sea can be difficult in high traffic zones, so ports have established elaborate vessel traffic services to monitor and direct ships into and out of port.[182]

The North Sea coasts are home to numerous canals and canal systems to facilitate traffic between and among rivers, artificial harbours, and the sea. The Kiel Canal, connecting the North Sea with the Baltic Sea, is the most heavily used artificial seaway in the world reporting an average of 89 ships per day not including sporting boats and other small watercraft in 2009.[183] It saves an average of 250 nautical miles (460 km; 290 mi), instead of the voyage around the Jutland peninsula.[184] The North Sea Canal connects Amsterdam with the North Sea.

See also

- European Atlas of the Seas

- List of languages of the North Sea

- North Sea Commission

- Northwestern Europe

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m L.M.A. (1985). "Europe". In University of Chicago (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica Macropædia. Vol. 18 (Fifteenth ed.). U.S.A.: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 832–835. ISBN 978-0-85229-423-9.

- ^ a b c d Ripley, George; Charles Anderson Dana (1883). The American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge. D. Appleton and company. p. 499. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Helland-Hansen, Bjørn; Fridtjof Nansen (1909). "IV. The Basin of the Norwegian Sea". Report on Norwegian Fishery and Marine-Investigations Vol. 11 No. 2. Geofysisk Institutt. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d "About the North Sea: Key facts". Safety at Sea project: Norwegian Coastal Administration. 2008. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Ray, Alan; G. Carleton; Jerry McCormick-Ray (2004). Coastal-marine Conservation: Science and Policy (illustrated ed.). Blackwell Publishing. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-632-05537-1. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Chapter 5: North Sea" (PDF). Environmental Guidebook on the Enclosed Coastal Seas of the World. International Center for the Environmental Management of Enclosed Coastal Seas. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Calow, Peter (1999). Blackwell's Concise Encyclopedia of Environmental Management. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-632-04951-6. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ "Limits in the seas: North Sea continental shelf boundaries" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. United States Government. 14 June 1974. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Ostergren, Robert Clifford; John G. Rice (2004). The Europeans: A Geography of People, Culture, and Environment. Bath, UK: Guilford Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-89862-272-0.

- ^ Dogger Bank. Maptech Online MapServer. 1989–2008. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ Tuckey, James Hingston (1815). Maritime Geography and Statistics ... Black, Parry & Co. p. 445. ISBN 9780521311915. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Bradford, Thomas Gamaliel (1838). Encyclopædia Americana: A Popular Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, History, Politics, and Biography, Brought Down to the Present Time; Including a Copious Collection of Original Articles in American Biography; on the Basis of the Seventh Edition of the German Conversations-lexicon. Thomas, Cowperthwait, & co. p. 445. ISBN 9780521311915. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Alan Fyfe (Autumn 1983). "The Devil's Hole in the North Sea". The Edinburgh Geologist (14). Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ The Walde Lighthouse is 6 km (4 mi) east of Calais (50°59′06″N 1°55′00″E / 50.98500°N 1.91667°E), and Leathercoat Point is at the north end of St Margaret's Bay, Kent (51°10′00″N 1°24′00″E / 51.16667°N 1.40000°E)

- ^ "North Sea cod 'could disappear' even if fishing outlawed". The Telegraph. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 September 2009.

- ^ "Global Warming Triggers North Sea Temperature Rise". Agence France-Presse. Terra Daily. 14 November 2006. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ Reddy, M. P. M. (2001). "Annual variation in Surface Salinity". Descriptive Physical Oceanography. Taylor & Francis. p. 114. ISBN 978-90-5410-706-4. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ "Met Office: Flood alert!". Met office UK government. 28 November 2006. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "Safety at Sea". Currents in the North Sea. 2009. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- ^ Freestone, David; Ton IJlstra (1990). "Physical Properties of Sea Water and their Distribution Annual: Variation in Surface Salinity". The North Sea: Perspectives on Regional Environmental Co-operation. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 66–70. ISBN 978-1-85333-413-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Dyke, Phil (1974). Modeling Coastal and Offshore Processes. Imperial College Press. pp. 323–365. ISBN 978-1-86094-674-5. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2008. p. 329 tidal map showing amphidromes

- ^ Carter, R. W. G. (1974). Coastal Environments: An Introduction to the Physical, Ecological and Cultural Systems of Coastlines. Academic Press. pp. 155–158. ISBN 978-0-12-161856-8. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2008. p. 157 tidal map showing amphidromes

- ^ Pugh, D. T. (2004). Changing Sea Levels: Effects of Tides, Weather, and Climate. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-521-53218-1. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020. p. 94 shows the amphidromic points of the North Sea

- ^ Tide table for Lerwick: tide-forecast Archived 26 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide table for Aberdeen: tide-forecast Archived 5 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide table for North Shields: tide-forecast Archived 26 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide tables for Kingston upon Hull: Tides Chart Archived 15 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine and Tide-Forecast Archived 7 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide table for Grimsby: Tide-Forecast Archived 7 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide tables for Skegness: Tideschart Archived 12 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine und Tide-Forecast Archived 7 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide tables for King's Lynn: Tideschart Archived 12 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine und Tide-Forecast Archived 7 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide tables for Hunstanton: Tideschart Archived 12 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Harwich". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for London". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ Tide tables for Dunkerque: Tides Chart Archived 15 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine and tide forecast Archived 6 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tide tables for Zeebrugge: Tides Chart Archived 15 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine and tide forecast Archived 6 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Antwerpen". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Rotterdam". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Ahnert. F.(2009): Einführung in die Geomorphologie. 4. Auflage. 393 S.

- ^ "Katwijk aan Zee Tide Times & Tide Charts". surf-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Den Helder". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Harlingen". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Borkum". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Windfinder.com – Wind, waves, weather & tide forecast Emden". Windfinder.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Wilhelmshaven". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Bremerhaven". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Guido Gerding. "Gezeitenkalender für Bremen, Oslebshausen, Germany (Tidenkalender) – und viele weitere Orte". gezeiten-kalender.de. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Gezeitenvorausberechnung". bsh.de. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ a b calculated from Ludwig Franzius: Die Korrektion der Unterweser (1898). suppl. B IV.: weekly average tide ranges 1879

- ^ telephonical advice by Mrs. Piechotta, head of department of hydrology, Nautic Administration for Bremen (WSA Bremen Archived 27 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Cuxhaven". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Hamburg". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Gezeitenvorausberechnung". bsh.de. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Westerland". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Gezeitenvorausberechnung". bsh.de. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Tidal tables". dmi.dk. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Tide Times and Tide Chart for Esbjerg, Denmark". tide-forecast.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Vannstand – Norwegian official maritime Information → English version Archived 29 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Development of the East Riding Coastline" (PDF). East Riding of Yorkshire Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "Holderness Coast United Kingdom" (PDF). EUROSION Case Study. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ a b Overview of geography, hydrography and climate of the North Sea (Chapter II of the Quality Status Report) (PDF). Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR). 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ a b c Wefer, Gerold; Wolfgang H. Berger; K. E. Behre; Eystein Jansen (2002) [2002]. Climate Development and History of the North Atlantic Realm: With 16 Tables. Springer. pp. 308–310. ISBN 978-3-540-43201-2. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ Oosthoek, K. Jan (2006–2007). "History of Dutch river flood defences". Environmental History Resources. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "North Sea Protection Works – Seven Modern Wonders of World". Compare Infobase Limited. 2006–2007. Archived from the original on 25 May 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Rosenberg, Matt (30 January 2007). "Dykes of the Netherlands". About.com – Geography. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- ^ a b c "Science around us: Flexible covering protects imperiled dikes – BASF – The Chemical Company – Corporate Website". BASF. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Peters, Karsten; Magnus Geduhn; Holger Schüttrumpf; Helmut Temmler (31 August – 5 September 2008). "Impounded water in Sea Dikes" (PDF). ICCE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ "Dune Grass Planting". A guide to managing coastal erosion in beach/dune systems – Summary 2. Scottish Natural Heritage. 2000. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Ingham, J. K.; John Christopher Wolverson Cope; P. F. Rawson (1999). "Quaternary". Atlas of Palaeogeography and Lithofacies. Geological Society of London. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-86239-055-3. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ Morin, Rene (2 October 2008). "Social, economical and political impact of Weather" (PDF). EMS annual meeting. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ "scinexx | Der Untergang: Die Grote Manndränke – Rungholt Nordsee" (in German). MMCD NEW MEDIA. 24 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ Coastal Flooding: The great flood of 1953. Investigating Rivers. Archived from the original on 26 November 2002. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Lamb, H. H. (1988). Weather, Climate & Human Affairs: A Book of Essays and (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 187. ISBN 9780415006743. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Bojanowski, Axel (11 October 2006). "Tidal Waves in Europe? Study Sees North Sea Tsunami Risk". Spiegel Online. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Bondevik, Stein; Sue Dawson; Alastair Dawson; Øystein Lohne (5 August 2003). "Record-breaking Height for 8000-Year-Old Tsunami in the North Atlantic". Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union. 84 (31): 289, 293. Bibcode:2003EOSTr..84..289B. doi:10.1029/2003EO310001. hdl:1956/729.

- ^ a b A tsunami in Belgium?. Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. 2005. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Ziegler, P. A. (1975). "Geologic Evolution of North Sea and Its Tectonic Framework". AAPG Bulletin. 59. doi:10.1306/83D91F2E-16C7-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- ^ See Ziegler (1990) or Glennie (1998) for the development of the paleogeography around the North Sea area from the Jurassic onwards

- ^ Torsvik, Trond H.; Daniel Carlos; Jon L. Mosar; Robin M. Cocks; Tarjei N. Malme (November 2004). "Global reconstructions and North Atlantic paleogeography 440 Ma to Recen" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ a b Glennie, K. W. (1998). Petroleum Geology of the North Sea: Basic Concepts and Recent Advances. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-632-03845-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Smith, A. G. (2004). Atlas of Mesozoic and Cenozoic Coastlines. Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–38. ISBN 978-0-521-60287-7. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Gibbard, P. (19 July 2007). "Palaeogeography: Europe cut adrift". Nature. 448 (7151): 259–60. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..259G. doi:10.1038/448259a. PMID 17637645. S2CID 4400105. (Registration is required)

- ^ Gupta, Sanjeev; Collier, Jenny S.; Palmer-Felgate, Andy; Potter, Graeme (2007). "Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel". Nature. 448 (7151): 342–5. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..342G. doi:10.1038/nature06018. PMID 17637667. S2CID 4408290.

- ^ Bradwell, Tom; Stoker, Martyn S.; Golledge, Nicholas R.; Wilson, Christian K.; Merritt, Jon W.; Long, David; Everest, Jeremy D.; Hestvik, Ole B.; Stevenson, Alan G.; Hubbard, Alun L.; Finlayson, Andrew G.; Mathers, Hannah E. (June 2008). "The northern sector of the last British Ice Sheet: Maximum extent and demise". Earth-Science Reviews. 8 (3–4): 207–226. Bibcode:2008ESRv...88..207B. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2008.01.008. S2CID 129790365. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ Sola, M. A.; D. Worsley; Muʼassasah al-Waṭanīyah lil-Nafṭ (2000). Geological Exploration in Murzuq Basin. A contribution to IUGS/IAGC Global Geochemical Baselines. Elsevier Science B.V. ISBN 9780080532462. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Lindsey, Kyle (25 April 2006). "Dinosaur of the Deep". Paleontology Blog. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "MarBEF Educational Pullout: The North Sea" (PDF). Ecoserve. MarBEF Educational Pullout Issue 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f "Quality Status Report for the Greater North Sea". Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR). 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Piet, G. J.; van Hal, R.; Greenstreet, S. P. R. (2009). "Modelling the direct impact of bottom trawling on the North Sea fish community to derive estimates of fishing mortality for non-target fish species". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 66 (9): 1985–1998. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsp162.

- ^ "Walrus". Ecomare. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Whales and dolphins in the North Sea 'on the increase'. Newcastle University Press Release. 2 April 2005. Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ^ Nienhuis, P.H. (2008). "Causes of the eelgrass wasting disease: Van der Werff's changing theories". Aquatic Ecology. 28 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1007/BF02334245. S2CID 37221865.

- ^ "Effects of Trawling and Dredging". Effects of Trawling and Dredging on Seafloor Habitat. Ocean Studies Board, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council. National Academy of Sciences. 2008. doi:10.17226/10323. ISBN 978-0-309-08340-9. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Tait, Ronald Victor; Frances Dipper (1998). Elements of Marine Ecology. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 432. ISBN 9780750620888. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "Extinct / extirpated species". Dr. Ransom A. Myers – Research group website. Future of Marine Animal Populations / Census of Marine Life. 27 October 2006. Archived from the original (doc) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Ray, C.E. (1960). "Trichecodon huxlei (Mammalia: Odobenidae) in the Pleaistocene of southeastern United States". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 122: 129–142.

- ^ "Atlantic Grey Whale". The Extinction Website. Species Info. 19 January 2008. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Brown, Paul (21 March 2002). "North Sea in crisis as skate dies out: Ban placed on large areas to stave off risk of species being destroyed". The Guardian. London, UK: Guardian Unlimited, Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Williot, Patrick; Rochard, Éric. "Sturgeon: Restoring an endangered species" (PDF). Ecosystems and territories. Cemagref. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (14 January 2016). "UK's last resident killer whales 'doomed to extinction'". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "OSPAR Convention". European Union. 2000. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ "Directive 2000/59/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2000 on port reception facilities for ship-generated waste and cargo residues". Official Journal of the European Communities. 28 December 2000. 28 December 2000 L 332/81. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2009. "Member States have ratified Marpol 73/78".

- ^ "Wadden Sea region case study" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage: A review of relevant experience in sustainable tourism in the coastal and marine environment, case studies, level 1, Wadden Sea region (Report). Stevens & Associates. 1 June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ Roller, Duane W. (2006). "Roman Exploration". Through the Pillars of Herakles: Greco-Roman Exploration of the Atlantic. Taylor and Francis. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-415-37287-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

Footnote 28. Strabo 7.1.3. The name North Sea – more properly 'Northern Ocean'. Septentrionalis Oceanus – probably came into use at this time; the earliest extant citation is Pliny, Natural History 2.167, 4.109.

- ^ "Morimarusa – Ancient Greek (LSJ)". lsj.gr. Archived from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Hartmann Schedel 1493 map (q.v.): Baltic Sea called "Mare Germanicum", North Sea called "Oceanus Germanicus"

- ^ Scully, Richard J. (2009). "'North Sea or German Ocean'? The Anglo-German Cartographic Freemasonry, 1842–1914". Imago Mundi. 62: 46–62. doi:10.1080/03085690903319291. S2CID 155027570.

- ^ Thernstrom, Stephan; Ann Orlov; Oscar Handlin (1980). Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-37512-3. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Looijenga, Tineke (2003). "Chapter 2 History of Runic Research". Texts & Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions. BRILL. p. 70. ISBN 978-90-04-12396-0. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b Cuyvers, Luc (1986). The Strait of Dover. BRILL. p. 2. ISBN 9789024732524. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ Green, Dennis Howard (2003). The Continental Saxons from the Migration Period to the Tenth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Frank Siegmund. Boydell Press. pp. 48–50. ISBN 9781843830269. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Smith, H. D. (1992). "The British Isles and the Age of Exploration – A Maritime Perspective". GeoJournal. 26 (4): 483–487. Bibcode:1992GeoJo..26..483S. doi:10.1007/BF02665747. S2CID 153753702.

- ^ Hansen, Mogens Herman (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. p. 305. ISBN 9788778761774. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Køppen, Adolph Ludvig; Karl Spruner von Merz (1854). The World in the Middle Ages. New York: D. Appleton and Company. p. 179. OCLC 3621972.

- ^ Ripley, George R; Charles Anderson Dana (1869). The New American Cyclopædia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge. New York: D. Appleton. p. 540. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Cook, Harold John (2007). Matters of Exchange: Commerce, Medicine, and Science in the Dutch Golden Age. Yale University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-300-11796-7. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b Findlay, Ronald; Kevin H. O'Rourke (2007). Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium. Princeton University Press. p. 187 and 238. ISBN 9780691118543.

- ^ MacDonald, Scott (2004). A History of Credit and Power in the Western World. Albert L. Gastmann. Transaction Publishers. pp. 122–127, 134. ISBN 978-0-7658-0833-2. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. New York: Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b Halpern, Paul G. (1994). A naval history of World War I. Ontario: Routledge. pp. 29, 180. ISBN 978-1-85728-498-0. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (September 2005) [2005]. World War I: Encyclopedia. Priscilla Mary Roberts. New York, US: ABC-CLIO. pp. 836–838. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Osborne, Eric W. (2006). The Battle of Heligoland Bight. London: Indiana University Press. p. Introduction. ISBN 978-0-253-34742-8. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer; Priscilla Mary Roberts (September 2005) [2005]. World War I: Encyclopedia. London: ABC-CLIO. pp. 165, 203, 312. ISBN 9781851094202. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Frank, Hans (15 October 2007) [2007]. German S-Boats in Action in the Second World War: In the Second World War. Naval Institute Press. pp. 12–30. ISBN 9781591143093. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "Atlantic, WW2, U-boats, convoys, OA, OB, SL, HX, HG, Halifax, RCN ..." Naval-History.net. Archived from the original on 13 January 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Kaffka, Alexander V. (1996). Sea-dumped Chemical Weapons: Aspects, Problems, and Solutions. North Atlantic Treaty Organization Scientific Affairs Division. New York, US: Springer. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7923-4090-4. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ It was, incidentally, the home of several Pirate Radio stations from 1960 to 1990. Johnston, Douglas M. (1976) [1976]. Marine Policy and the Coastal Community. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-85664-158-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "Forth Ports PLC". 2008. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ a b c Barry, M., Michael; Elema, Ina; van der Molen, Paul (2006). Governing the North Sea in the Netherlands: Administering marine spaces: international issues (PDF). Frederiksberg, Denmark: International Federation of Surveyors (FIG). pp. 5–17, Ch. 5. ISBN 978-87-90907-55-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ About the Common Fisheries Policy. European Commission. 24 January 2008. Archived from the original on 14 July 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "Text of the UN treaty" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ North Sea Continental Shelf Cases. International Court of Justice. 20 February 1969. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Pratt, J. A. (1997). "Ekofisk and Early North Sea Oil". In T. Priest, & Cas James (ed.). Offshore Pioneers: Brown & Root and the History of Offshore Oil and Gas. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-88415-138-8. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ a b Lohne, Øystein (1980). "The Economic Attraction". The Oil Industry and Government Strategy in the North Sea. Taylor & Francis. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-918714-02-2. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "TOTAL E&P NORGE AS – The history of Fina Exploration 1965–2000". About TOTAL E&P NORGE > History > Fina. Archived from the original on 7 October 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ McKetta, John J. (1999). "The Offshore Oil Industry". In Guy E. Weismantel (ed.). Encyclopedia of Chemical Processing and Design: Volume 67 – Water and Wastewater Treatment: Protective Coating Systems to Zeolite. CRC Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8247-2618-8.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "On This Day 6 July 1988: Piper Alpha oil rig ablaze". BBC. 6 July 1988. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "Statpipe Rich Gas". Gassco. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "North Sea Brent Crude". Investopedia ULC. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "North Sea". Country Analysis Briefs. Energy Information Administration (EIA). January 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ "Shell to cut 250 onshore jobs at its Scotland North Sea operations". Yahoo Finance. 12 August 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "Number offshore rigs worldwide by region 2018". Statista. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ Sherman, Kenneth; Lewis M. Alexander; Barry D. Gold (1993). Large Marine Ecosystems: Stress, Mitigation, and Sustainability (3, illustrated ed.). Blackwell Publishing. pp. 252–258. ISBN 978-0-87168-506-3. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ "MUMM – Fishing". Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. 2002–2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ "One Million Tons of North Sea Fish Discarded Every Year". Environment News Service (ENS). 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Clover, Charles (2004). The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-189780-2.

- ^ "North Sea Fish Crisis – Our Shrinking Future". Part 1. Greenpeace. 1997. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Olivert-Amado, Ana (13 March 2008). The common fisheries policy: origins and development. European Parliament Fact Sheets. Archived from the original on 22 March 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

- ^ a b "Cetaceans and Belgian whalers, A brief historical review" (PDF). Belgian whalers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ Lindquist, O. (2000). The North Atlantic grey whale (Escherichtius [sic] robustus): An historical outline based on Icelandic, Danish-Icelandic, English and Swedish sources dating from ca 1000 AD to 1792. Occasional papers 1. Universities of St Andrews and Stirling, Scotland. 50 p.

- ^ Scheinin, Aviad P; Aviad, P.; Kerem, Dan (2011). "Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) in the Mediterranean Sea: anomalous event or early sign of climate-driven distribution change?". Marine Biodiversity Records. 2: e28. Bibcode:2011MBdR....4E..28S. doi:10.1017/s1755267211000042 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Phua, C.; S. van den Akker; M. Baretta; J. van Dalfsen. "Ecological Effects of Sand Extraction in the North Sea" (PDF). University of Porto. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Rice, Patty C. (2006). Amber: Golden Gem of the Ages: Fourth Edition (4, illustrated ed.). Patty Rice. pp. 147–154. ISBN 978-1-4259-3849-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ LTI-Research Group; LTI-Research Group (1998). Long-term Integration of Renewable Energy Sources into the European Energy System. Springer. ISBN 978-3-7908-1104-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ The European offshore wind industry -key trends and statistics 1st half 2013 Archived 30 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine EWEA 2013

- ^ Moss, Joanne "Critical perspectives: North Sea offshore wind farms.: Oral histories, aesthetics and selected legal frameworks relating to the North Sea." (2021) https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1611092/FULLTEXT01.pdf Archived 24 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2 October 2023

- ^ "New Research Focus for Renewable Energies" (PDF). Federal Environment Ministry of Germany. 2002. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Ecology Consulting (2001). "Assessment of the Effects of Offshore Wind Farms on Birds" (PDF). United Kingdom Department for Business, Enterprise, & Regulatory Reform. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Study finds offshore wind farms can co-exist with marine environment Archived 16 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Businessgreen.com (26 January 2009). Retrieved on 5 November 2011.

- ^ Future Leasing for Offshore Wind Farms and Licensing for Offshore Oil & Gas and Gas Storage Archived 22 May 2009 at the UK Government Web Archive. UK Offshore Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment. January 2009 (PDF). Retrieved on 5 November 2011.

- ^ Kaiser, Simone; Michael Fröhlingsdorf (20 August 2007). "Wuthering Heights: The Dangers of Wind Power". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ "Centrica warns on wind farm costs". BBC News. 8 May 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ "Centrica seeks consent for 500MW North Sea wind farm". New Energy Focus. 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gow, David (4 September 2008). "Greenpeace's grid plan: North Sea grid could bring wind power to 70m homes". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ Wynn, Gerard (15 January 2009). "Analysis – New EU power grids in frame due to gas dispute". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "North Sea Infrastructure". TenneT. March 2017. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Billia Croo Test Site". EMEC. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Fall of Warness Test Site". EMEC. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Prototype testing in Denmark". Wave Dragon. 2005. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Wong, P. P. (1993). Tourism Vs. Environment: The Case for Coastal Areas. Springer. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7923-2404-1. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ a b Hall, C. Michael; Dieter K. Müller; Jarkko Saarinen (2008). Nordic Tourism: Issues and Cases. Channel View Publications. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-84541-093-3. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ "St. Andrews, Scotland: See the place where golf was born and Will and Kate fell in love". USA Today. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

Tiny St. Andrews has a huge reputation, known around the world as the birthplace and royal seat of golf. The chance to play on the world's oldest course – or at least take in the iconic view of its 18th hole – keeps the town perennially popular among golfing pilgrims

- ^ "Welcome North Sea Trail". European Union. The North Sea Trail/NAVE Nortrail project. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Knudsen, Daniel C.; Charles Greet; Michelle Metro-Roland; Anne Soper (2008). Landscape, Tourism, and Meaning. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-7546-4943-4. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Schulte-Peevers, Andrea; Sarah Johnstone; Etain O'Carroll; Jeanne Oliver; Tom Parkinson; Nicola Williams (2004). Germany. Lonely Planet. p. 680. ISBN 978-1-74059-471-4. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Büsum: The natural healing power of the sea. German National Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "World Port Rankings" (PDF). American Association of Port Authorities. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "Port Authority Bruges-Zeebrugge". MarineTalk. 1998–2008. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- ^ "The Dover Strait". Maritime and Coastguard Agency. 2007. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Freestone, David (1990). link (ed.). The North Sea: Perspectives on Regional Environmental Co-operation. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 186–190. ISBN 978-1-85333-413-9. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ "Kiel Canal". Kiel Canal official website. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "23390-Country Info Booklets Hebridean Spirit The Baltic East" (PDF). Hebridean Island Cruises. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

General references

- "North Sea Facts". Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Management Unit of North Sea Mathematical Models. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

Further reading

- Dickson, Henry Newton (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). pp. 786–787.

- Ilyina, Tatjana P. (2007). The fate of persistent organic pollutants in the North Sea multiple year model simulations of [gamma]-HCH, [alpha]-HCH and PCB 153Tatjana P Ilyina;. Berlin; New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-68163-2.